Photo by Anthony Tori on Unsplash

Overview

This article provides an introduction to Promises in JavaScript, including how to handle fulfilled and rejected states, how to chain promises, and how to use the async/await syntax to write cleaner code. Code examples and explanations are interspersed throughout, as well as an example using the promise-based fetch API to retrieve resources from a remote server/API.

Some prior knowledge of JavaScript and HTML is expected as the article progresses.

What is a Promise and How Does It Work?

Promises in JavaScript (JS) work in a similar way to the promises we make to each other every day. When I promise to wash your car, you expect it to be done, or at least for me to explain why it wasn't.

According to the MDN docs:

"The Promise object represents the eventual completion (or failure) of an asynchronous operation and its resulting value."

Let's break that down and apply it to our real-world scenario:

- "The promise object" - this is the promise that I make to you.

- "The eventual completion (or failure)" - I will either succeed or fail.

- "An asynchronous operation" - the task of cleaning the car.

- "Its resulting value" - my response after attempting the task.

Once I've made the promise, you'll want to check on the progress. My response might be one of the following:

- I have not started.

- I am done.

- I tried but failed because...

Similarly, a JS Promise has three states (MDN docs):

- "Pending" - initial state, neither fulfilled nor rejected.

- "Fulfilled" - meaning that the operation was completed successfully.

- "Rejected" - meaning that the operation failed.

Code Example

Let's apply our real-world scenario to code:

new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => resolve('I am done'), 1000);

});

Explanation

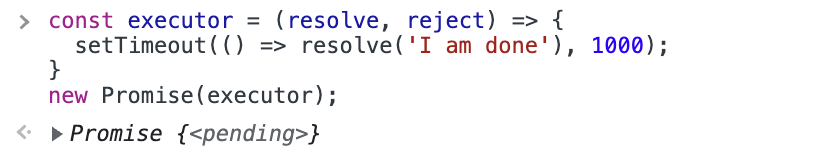

We have created a Promise object using new Promise() (Promise constructor). This is equivalent to me making a promise to clean your car.

We also pass an anonymous executor function into the Promise constructor. The executor is effectively me; I'm the person who will clean the car. As programmers, we write this function ourselves. We could just as easily write it like this:

const executor = (resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => resolve('I am done'), 1000);

}

new Promise(executor);

You'll notice that the executor (now a named function) receives two parameters: resolve and reject. These parameters are actually methods belonging to the Promise object that are passed into the executor. In our analogy, as I'm effectively the executor, I would use these methods to update the state of my progress. For example:

- Is the task done?

resolve(). - Did something go wrong?

reject().

Within the executor, we use setTimeout with a 1-second delay. This simulates the act of cleaning the car (a very quick job!) but in JS terms, we are simulating an asynchronous operation (MDN docs).

Inside the setTimeout statement, we call resolve() to update the state of the promise, passing a string value of “I am done”. This could be considered my response to you.

Paste the code into your browser console and hit the enter key:

A Promise object has been returned that seems to indicate a 'pending' state. Shouldn't we see the resolved string value, ‘I am done’? Was our executor function invoked?

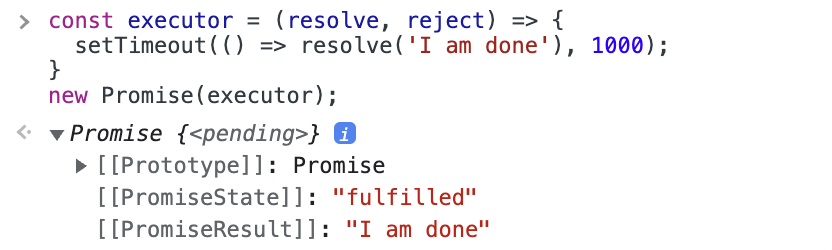

Open up the Promise object in the console.

Our executor function has indeed been invoked, as indicated by the PromiseState ("fulfilled") and PromiseResult ("I am done").

So why did we see 'pending' in the console? Remember the MDN docs?

"pending: initial state, neither fulfilled nor rejected."

The 'pending' value is the state of the promise at the point that it was created. Remember, the executor function contains a setTimeout of 1 second. Therefore, one second after we hit enter, PromiseState and PromiseResult will be updated.

So, if the promise has been successfully resolved, how do we access the result? And, considering I've spent 1 second cleaning your car, what if you're not happy with the job?

Promise chaining

Your car is still dirty, so you ask me to clean it properly.

Code example

const cleanTheCar = (resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => resolve('car cleaned in 1 second'), 1000);

}

const cleanTheCarProperly = () => {

setTimeout(() => console.log('car cleaned properly'), 2000);

}

const handleSuccess = (result) => {

if (result === 'car cleaned in 1 second') {

return cleanTheCarProperly();

}

};

new Promise(cleanTheCar)

.then(handleSuccess);

Explanation

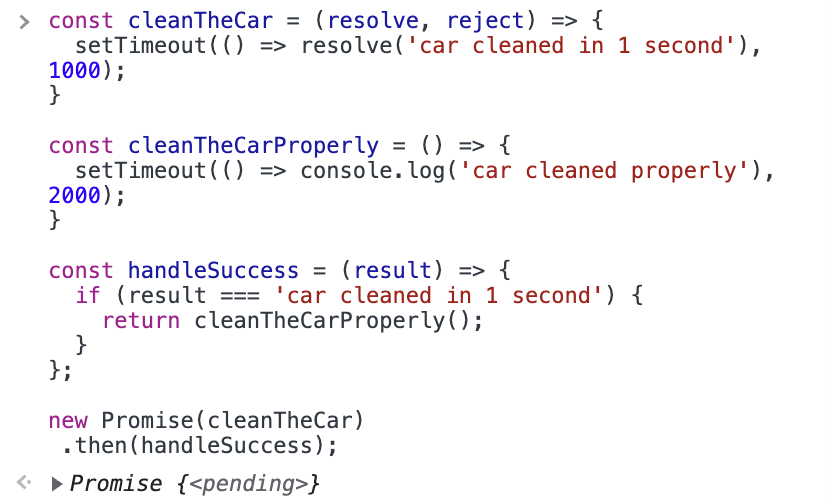

We have rewritten our original example, creating two executor functions - cleanTheCar and cleanTheCarProperly - plus a new function named handleSuccess (a callback function).

As before, we pass the first executor - cleanTheCar - to the promise constructor, but this time we chain a then() method at the end.

then() is a method of the promise object. In short, it listens for the use of resolve() or reject() and will itself return a promise. Using then() is like saying, "catch the value of resolve() or reject() and give it to me". This is how we access the PromiseResult (as seen in the console example above).

Within then(), we pass the handleSuccess callback function. It receives the result parameter and uses an if statement to check the value (which should be the string 'car cleaned in 1 second'). The if statement is effectively you checking the car, seeing it's still dirty, and sending me back to clean the car properly.

By returning the cleanTheCarProperly function from then(), we are effectively passing an executor function to a new promise. The function is invoked, and the string value 'car cleaned properly' is displayed in the console.

So far we have looked at the fulfilled case of a JS promise - what about the rejected case?

Handling rejections and errors

- What causes a rejection or error?

- How do we handle the

rejectedstate?

Our ‘clean the car’ analogy has been useful but we’ll now consider a scenario in the context of web development.

Code example

Below is a simple HTML page with some JS that uses a promise to display an image or error message (this jsfiddle will help for testing purposes).

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Load Profile Image</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Profile image</h1>

<script>

const loadImage = (resolve, reject) => {

const img = new Image();

img.src = 'https://picsum.photos/420/320?image=0';

img.onload = () => {

resolve(img.src);

};

img.onerror = () => {

reject('Failed to load image');

};

}

const handleFulfilled = (result) => {

const image = document.createElement('img');

image.src = result;

document.body.appendChild(image);

};

const handleRejected = (error) => {

const h2 = document.createElement("h2");

const textNode = document.createTextNode(error);

h2.appendChild(textNode);

document.body.appendChild(h2);

};

new Promise(loadImage)

.then(handleFulfilled, handleRejected);

</script>

</body>

</html>

Explanation

Within the script tags above we have 3 functions, our promise executor - loadImage - and 2 callback functions: handleFulfilled and handleRejected.

We pass our executor to the promise constructor as usual but this time we pass both callback functions to then().

“The then() method of [Promise](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/Promise) instances takes up to two arguments: callback functions for the fulfilled and rejected cases of the Promise.” (MDN docs)

This effectively answers our 2nd question: How do we handle the ‘rejected’ state?

We can handle the rejected state of a promise by passing a 2nd callback function to then() that receives the value of reject() if invoked in the promise executor (loadImage). We’ll explore this way of handling rejections for now but there is a better way.

Run the jsfiddle to trigger the fulfilled journey before we explore the rejected journey:

fulfilled journey

- The

htmlandheadtags are parsed - The

bodytag is parsed - The

scripttags execute our JS code - Functions are created:

loadImage,handleFulfilledandhandleRejected - A new promise object is created and the

loadImagepromise executor is invoked imgis declared and assigned and image object- The

img.srcprop is assigned a url and the browser begins downloading the image - The image downloads successfully:

img.onloadis triggered, callingresolve()that updatesPromiseStatetofulfilledandPromiseResultto the original url inimg.src - The use of

resolve()triggers thehandleFulfilledcallback, passing it the value ofPromiseResultas theresultparameter - An

imageelement is created in the DOM - The

image.srcprop is passed the value ofresult - The

imageelement is appended to thebody - The image is visible in the browser

rejected journey

Now, in the jsfiddle, delete one or more characters from the img.src string to force a failure when downloading the image. The rejected journey will be similar to fulfilled:

- (Steps 1-7 are repeated from ‘Fulfilled journey’)

- The image fails to download:

img.onerroris triggered, callingreject()to updatePromiseStatetorejectedandPromiseResultto‘Failed to load image' - The use of

reject()triggers thehandleRejectedcallback, passing it the value ofPromiseResultas theerrorparameter - A

h2element is created in the DOM - A

textNodeis created in the DOM and passed the value oferror(‘Failed to load image') - The

textNodeis appended to theh2element - The

h2is appended to thebody - The error message

‘Failed to load image’is visible in the browser

The above partly answer’s the question, ‘What might cause a rejection or error?’ in that we as programmers can define when a rejection occurs. However, mistakes can be made in code, how do we handle these errors?

Errors in our code

In loadImage (see jsfiddle) where we have assign an image object to the variable img let’s force an error in our code by naming it im instead:

...

const loadImage = (resolve, reject) => {

const im = new Image(); // <<< forced error

img.src = 'https://picsum.photos/420/320?image=0';

img.onload = () => {

resolve(img.src);

};

img.onerror = () => {

reject('Failed to load image');

};

}

...

After making this change, run the fiddle again and ‘ReferenceError: im is not defined’ will be displayed on the page. This is useful, we now know our handleRejected callback will be invoked when there are mistake in our code.

However, what if an error occurs in the handleRejected callback itself? Surely that error will go unhandled?

Error handling with catch()

Promise rejections are simply errors, moments where things go wrong, whether we’ve explicitly invoked reject() or there’s an error elsewhere in the code. Rejections can be handled in a then() block but a better approach would be to chain a catch() block.

The benefits are:

- Clarity: a

catch()block allows us to handle rejections/errors in one place,then()blocks only need to handle fulfilled cases, i.e. our code is easier to read - Adhering to the DRY principle: Handling rejections in multiple chained

then()blocks would mean passing ourhandleRejectedcallback N times while acatch()block receives the callback only once - Unhandled rejections: If we failed to add a

handleRejectedcallback to a chainedthen()block or if an error occurred within thehandleRejectedcallback itself, these would simply go unhandled, i.e. adding a catch block ensures that all errors are caught and handled properly

To implement a catch() block we simply re-write the promise chain:

...

new Promise(loadImage)

.then(handleFulfilled)

.catch(handleRejected);

..

async/await instead of promise chains

The MDN docs note some common mistakes when using promise chains. One way of avoiding them is to use the async/await syntax mixed with try…catch blocks. I personally prefer this approach for readability and use it wherever possible.

Below is a re-write of our current ‘Load Profile Image’ example and here’s a new jsfiddle.

This time, instead of using the Image() constructor we use the browser’s native fetch API to download the image. Fetch is promised-based, supported by most modern browsers and commonly used to retrieve data/resources from a remote server/API.

Code example

...

<script>

const handleFulfilled = async (src) => {

const image = document.createElement('img');

image.src = src;

document.body.appendChild(image);

};

const handleRejected = async (error) => {

const h2 = document.createElement("h2");

const textNode = document.createTextNode(error);

h2.appendChild(textNode);

document.body.appendChild(h2);

};

const handleFetchImage = async () => {

try {

const imageUrl = 'https://picsum.photos/420/320?image=0';

const response = await fetch(imageUrl);

const blob = await response.blob();

const image = URL.createObjectURL(blob);

await handleFulfilled(image);

} catch (error) {

await handleRejected(error);

}

};

handleFetchImage();

</script>

...

Explanation

First thing to note is we’re no longer using the Promise constructor. The fetch API is promise-based, i.e. under the hood it returns a promise that handles the use of resolve() and reject() for us.

Secondly, we’re using the async and await keywords throughout the code.

Thirdly, handleFetchImage utilises a try…catch block.

By declaring handleFetchImage as an async function we can use the await keyword within it to literally wait for the result. The await keyword is like chaining a then() onto any promise but only to get the fulfilment value (MDN docs). This combination allows us to write promise based code in a more succinct manner, i.e. without the need for numerous promise chains.

Now, when the script tags are parsed in our new jsfiddle, our async functions are created - handleFulfilled, handleRejected and handleFetchImage - and handleFetchImage is invoked.

Let’s step through handleFetchImage:

Fulfilled journey

- Wraps everything in a

try/catchblock to handle errors/rejections, i.e. fetch is promise-based so it will triggerreject()for us - Declares an

imageUrlstring (the remote location of the image) - Declares a

responsevariable thatawait’s the result offetch's attempt to retrieve theimageUrl - The fetch API returns a response object so we must extract the the

blobdata and convert that into aimageBlobUrlobject - Finally, we pass

imageBlobUrlto ourhandleFulfilledcallback (that is nowasync) and weawaitthis function too (by waiting for the code within to execute, any errors that occur will be caught/handled in ourcatchblock) - The image is visible in the browser

Rejected journey

In our new jsfiddle, delete one or more characters in the imageUrl string to force a rejection in fetch.

- (Steps 1-73 are repeated from ‘Fulfilled journey’)

fetchfails to get the image triggering areject(’TypeError: Failed to fetch’)statement (this rejection is hidden away in the fetch API)- The rejection is caught in our

catchblock and passed to thehandleRejectedcallback (nowasync) which weawait handleRejectedreceives theerrorparameter (originating fromreject()withinfetch) and appends it to the pagebody- The error message

‘TypeError: Failed to fetch’is visible in the browser

The await operator is the equivalent of then() (albeit in a cleaner syntax) allowing us to sequentially move from one promise to the next, checking the results if needed and making decisions as we go.

The only issues I had with async/await are simply remembering to use the keywords when either declaring a function - async - or accessing the result of one - await.

Conclusion

Promises in JavaScript are extremely useful because they allow you to write asynchronous code that can handle time-consuming tasks (such as retrieving data) without blocking the main thread of your application.

Part 2 (coming soon…) will explore some advanced uses of Promises not only in the browser but in backend Node.js environments too.